Forecast Form

Art in the Caribbean Diaspora, 1990’s - Today

(Originally published by The Brooklyn Rail)

Zilia Sánchez, Lunar con Tatuaje, c. 1968/96. Acrylic and ink on canvas, 71 × 72 × 12 inches. Courtesy Zilia Sánchez and Galerie Lelong & Co., New York. © Zilia Sánchez.

The complexities of the Caribbean expand beyond historical commonalities and cultural ties. Rather than attempt to condense artwork emerging from this region and its diaspora into a superficial idea of shared themes and visual representations, Forecast Form: Art in the Caribbean Diaspora 1990s to Today weaves a far richer conversation that explores a multitude of distinct voices. The exhibition engages the Caribbean across various locations and temporalities, delving into modes of thought, being, and responses that emanate from the complexities and varying conceptions of the region. Thoughtfully curated by Carla Acevedo-Yates at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, with curatorial assistant Iris Colburn, and curatorial fellows Isabel Casso and Nolan Jimbo, the exhibition is rhizomatic in its threads of critique and reflection, using the dynamism of the weather as a metaphor to bring together thirty-seven artists who are invested in both the potential and contradictions of the Caribbean.

There is a measured pacing throughout the exhibition with subtle connections between works in each room, an attention to intricate visual conversations and notes of abstraction. The composition of lines on Zilia Sánchez’s sculptural, bodily landscape Lunar con tatuaje (1968–69) gestures to the labyrinth of detailed marks in Tomm El-Saieh’s Cursive Grid (2017–18) and are complemented by the layering of faint images abstracted into the ruby, magenta, and vermillion hues of Frank Bowling’s Bartica (1968–69). Inconspicuously positioned throughout Forecast Form are photographs from Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Works in Mexico (1973–77), each imbued with the absence-presence that the artist often explored and a haunting amplified after her death. Mendieta’s silhouette photographs ground the other works around them, such as the bodily articulation in the sand filled with seaweed that speaks to the cyclical ebb and flow of the ocean tide in Zilia Sánchez’s video encuentrismo-ofrenda o retorno (2000), an exchange of offerings between the water and the shore.

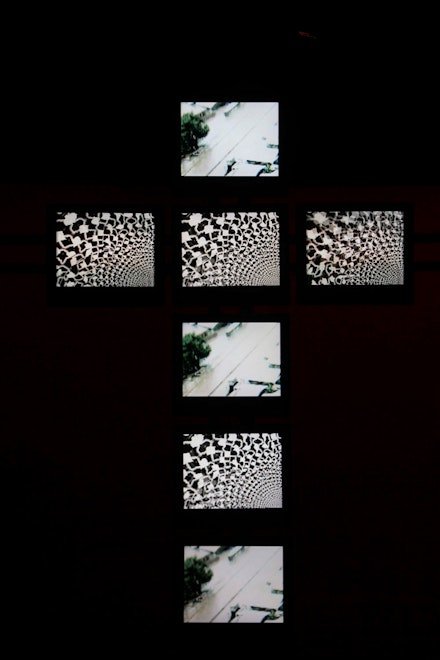

Maksaens Denis, Kwa Bawon, 2004. Iron structure with seven monitors, Approx. 144 × 72 inches. Courtesy the artis

How does one confront the continued social and economic effects of anti-Blackness in a region forged through the inconceivable violence of Trans-Atlantic slavery? In a looming installation that spans an entire wall of the museum, Marton Robinson’s La Coronación de la Negrita (2022) draws on the iconography of La Negrita (or the Black Virgin), the patron saint of Costa Rica. Surrounded by figures alluding to Black and indigenous life in the country, La Negrita holds a child that references the racist imagery from the famous children’s book Cocorí. Robinson interrogates the prevalence of anti-Black and anti-indigenous sentiments throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, reorienting these figures to question the cultural frameworks of the nation. The stark contrast of white chalk on the black canvas background, which towers over the viewer, creates an ominous atmosphere across the gallery. This intensifies the jarring archival footage in Maksaens Denis’s Kwa Bawon (2004), an installation of video monitors arranged like a crucifix, citing the Haitian Vaudou symbolism of Baron Samedi that splices together footage from Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s tumultuous presidential terms in Haiti with the chaos of Hurricane Jean that ravaged the country in 2004. The piece contends with the Western supported political corruption and anti-Black conditions that perpetually target Haitian people. Similar questions are taken up by artists Daniel Lind-Ramos, Cosmo Whyte, and Firelei Báez, who incorporate historical references to affirm the position of Black life amidst denigration and socio-cultural whitening (or blanqueamiento) in the region.

Metaphors of water and fluidity dominate descriptions of the Caribbean to characterize the intermixture of people, cultures, and the significance of the sea. Fluidity is also about dispersal; for as many people who remain in the Caribbean, the same or more have left, often not by choice. Diaspora is often shaped by imagined and ephemeral connections, ideas that animate Denzil Forrester’s 1985 painting Night Strobe with fleeting moments on the dancefloor charged by the musical genres of Reggae and Soca that manifest what “home” can be. Suchitra Mattai’s tapestry An Ocean Cradle (2022) centers on histories of exploitative indentured servitude that brought Indian migrants to Guyana, highlighting how African and South Asian cultures are interlaced now into the fabric of the Caribbean like the vintage handmade saris in the piece. Including artists such as Alia Farid, who is Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican, and David Medalla from the Philippines reconsiders the geographic boundaries of the region. Lorraine O’Grady’s The Fir-Palm (1991/2019) and The Strange Taxi: From Africa to Jamaica to Boston in 200 Years (1991/2019) serve similarly as a diasporic reminder, reaffirming the famed artist’s Jamaican heritage which is not often discussed.

Jeanette Ehlers, Black Bullets, 2012. Single-channel projection, 4 minutes, 33 seconds. Sound: Trevor Mathison; Technical Assistance: Markus von Platen; Camera: Jette Ellgaard & Jeannette Ehlers. Private collection.

Demands for idyllic excess and the extraction of natural resources have signified outside perspectives on the Caribbean, and these issues are considered in María Magdalena Campos-Pons Sugar/Bittersweet (2010) and Deborah Jack’s video installation the fecund, the lush and the salted land waits for a harvest…her people…ripe with promise, wait until the next blowing season (2022). In a meticulously assembled sculptural installation, Campos-Pons places West African spears that she has collected over years on small stools; each spear encircled by sugar discs created through glassblowing techniques. The artist grapples with the ruthless, extractive impacts of sugar production on the Caribbean, which serve as a foundation for modern global economies. There is a tension between the desire to get closer to the sugar discs and the instinct to stay back, driven by the combative nature of the spears, that emphasizes the underlying frictions explored throughout the exhibition, and which are often obscured in the commodification of the Caribbean. The installation projects the perverse beauty of the sugarcane fields—the underlying violence embedded in many of the landscapes that have become synonymous with the region. In a dreamlike divergence, Jeannette Ehlers’s video Black Bullets (2012) guides the viewer to an elsewhere in the clouds as Black figures walk into disappearance, a remembrance to the worlds made possible through the Haitian Revolution.

Acevedo-Yates writes that “Forecast Form proposes the Caribbean as a way of “thinking, being and doing.” The exhibition digs into this proposition as a rumination on the multiplicity that underpins the Caribbean. The show teases at the imaginary of the region rather than staking some claim to define or demand that the Caribbean be recognized as “this is who we are.” Though I had hoped to see more risks taken to include more artists from lesser-discussed countries in the Caribbean that continue to be overlooked, the exhibition is deeply generative in its refusal to be confined. In a roundtable discussion with Acevedo-Yates, artists María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Christopher Cozier, and Teresita Fernández each expressed in their own terms that there can be no simplified, unitary view of the Caribbean. Forecast Form will play a vital role in this shift.