Mementos of Desire

Reflections on Patric McCoy’s photographic archive of Black men in 1980’s Chicago

Patric McCoy and I sit across from each other, a binder of photographs resting on the table between us among stacked books of fiction, art, and memoir. I am perched on the edge of the couch, while he leans into an armchair. From the corner of my eye, I see a slide show with images of Black men cycle through on a computer screen, accompanied by the faint sound of jazz. We have not seen each other in a while, so we catch up, and I share more about my upcoming move to New York City. Emotion catches in my throat because it is still hard to talk about leaving Chicago. On this October afternoon, my thoughts are colored by an urgency to record our conversation before I can no longer easily enter the warm embrace of Patric’s home in Hyde Park. While we speak, one of his friends moves around in the kitchen, preparing fried fish that we will share later that evening.

Patric was born and raised in Chicago. His father was an artist, and he has long had a sense for the value of creative practice. Though he worked as an environmental scientist for the entirety of his professional career, he developed an extensive photography practice, first using a point-and-shoot camera during the 1960’s and ’70s to create images with family and friends. In the early ’80s, Patric became more focused in his photography and he learned to use a 35mm camera. He made a commitment to carry his camera everywhere he went and take at least one photograph per day. Most of the photographs from this period are of Black men throughout Chicago. He rode his bicycle to work downtown, and around different areas on the South Side. While biking, men would notice his camera and often approach him, asking to have their picture taken.

“I commuted to work on a bicycle, so I was riding through these neighborhoods in Chicago from the South Side all the way to the downtown area with this camera always visible, hanging off my neck. I’d be riding and people on the street would just holler out at me: ‘Hey, take my picture!’ It was almost always men. In fact, I might have five images of women out of the thousands and thousands of images of people who asked me to take their pictures. So, I would stop and take their picture and it often led to: ‘Hey, what’s up with you…?’ It was a come on. They were asking out of desire, a desire to be recorded, but I also think a desire to interact.”

Over the course of the 1980’s, Patric amassed an archive of thousands of photographs of the men he encountered. Prominent locations in the archive include Jackson Park, which straddles the Woodlawn, Hyde Park, and South Shore communities, and which was (and still is) known for cruising. Another key spot is the dive bar, the Rialto Tap in the South Loop, where Black men from across the city would come to hang out, and potentially hook up. The Rialto, as Patric describes it, was in one of the seediest areas downtown, alongside homeless shelters, single occupancy lodging and burlesque clubs. A bar where “anything goes”, he recalls, “So the ‘good people’ would never say that they went to the Rialto, but they would go there… the Rialto had the reputation of being a place where you could smoke marijuana openly at the bar just like you’d smoke cigarettes…the police didn’t even do anything. The latter half of the 80’s was when the bar itself started to accept the fact that it was gay. I think they even had a float in the gay pride parade one time.”

Interlude

His head is turned to the right as he looks past the camera, lips calmly closed and a chain with a pendant around his neck. Wearing a white tank top, arms crossed in front of his chest, he leans on the back of a light-yellow car. The scaffolding of the CTA tracks project above his head, perhaps an indicator of Downtown Chicago. He seems at ease as he is photographed.

In Patric’s photographs, some men pose or look straight into the camera; others appear more candidly, in mid-conversation, moving around the bar, or on the street. There is no specific “type” of man in the photographs, with race being the only throughline. When I linger on certain images, Patric is quick to remark, “he was a freak”, signaling sexual disposition, and disrupting any narrow idea about who any of the men may be. He has a glint in his eyes as he recounts some of the raunchier memories—of muscular men bent over in bar bathrooms waiting for whomever entered—stressing that no matter how masculine someone appeared, what they enjoyed when it came to sex could never be assumed. Looking at another image, Patric recalls: “These two look like regular guys, but you’d never know, they were rival gang members who would hang at the Rialto with this tough attitude…but both were basically queens.” The landscape of Chicago through Patric’s eyes is charged with the sexual encounters that transpired there. I return to Jose Esteban Muñoz’s essay, “Ephemera as Evidence,” to muse on the feelings and memories etched into place, an awareness of which connects those with shared experiences who look beyond what meets the eye. He describes queer experience as often existing through ephemerality, “linked to alternate modes of textuality and narrativity like memory and performance: it is all of those things that remain after a performance, a kind of evidence of what has transpired but certainly not the thing itself” (1996:10). [1] Embedded in Patric’s portraits is a visual mapping of erotic desire for a generation of Black men in Chicago, the places they frequented and the desires they pursued.

An Archive Layered with Pleasure

Spending time with Patric McCoy, his photographs beside him and guided by his words, nurtures a textured insight that calls the archive to life through glimpses into memory. The moments that extend beyond the static image are conjured in my mind, infused with feeling by the dynamism of his reflections. So, while I first intended to approach this essay on his photographic archive with the anxiety to “say something new” and delve into what may have been overlooked, returning to our conversations was the reminder to simply listen to what he said, to lean into the pushback he gave to certain questions, and let the desires that animate the images lead the writing. Patric’s directness is generative, clear that the pursuit of pleasure is central to the archive, while recognizing that each viewer will have their own experience. I hold onto the vitality of his conception not as a superficial reading of the images but an affirmation of the various relations amongst the men pictured through their different articulations of desire.

Expansive lives populate these images, as is the case with all archives. I ask Patric what ignited his focus on Black men, and he swiftly replies: “Because those are the men I am attracted to.” His response reminds me of conversations I have had with my friend Ajamu X, a photographer whose work is critical to the history of image making intersecting with queer life in the U.K., particularly Black queer histories. Ajamu’s practice is rooted in his insistence, “we must talk about pleasure!” Similarly to Patric, Ajamu maintains that pleasure is critical to one’s understanding of self, even though it is relegated outside of deep study and reflection.

“Photography was always taking second fiddle to having sex.” Patric’s response pushed me to consider the physicality of sex as fundamental to his creative practice. In the interview, “Promiscuous Archiving: Notes on the Joys of Curating Black Queer Legacies,” Ajamu X elaborates on the “mischievous” potential of the term promiscuous as it relates to archives, noting the connection to the transient, sensuous, and playful aspects of Black queer histories. For Ajamu, sexuality often is discussed within the archive while sterilizing it of the sex itself: “This is where the mess, sweat, dirt takes place. There is a refusal to talk about that “nasty” stuff in public…We talk about sexuality but not the sucking, the fucking, and so on. We try to dress these things up nice and neatly. It still needs to be dirty” (588, 2018). [2] Patric’s work is a mode of promiscuous archiving, layered with pleasure. Sex informs his acute attention to detail: “I was having a lot of sex, I was seeing a lot of men…I got to really develop an eye.” I take in the potency of the images as he reflects on the broader interactions that accompanied them. Although most of the images are not explicitly sexual, they are latent with lust.

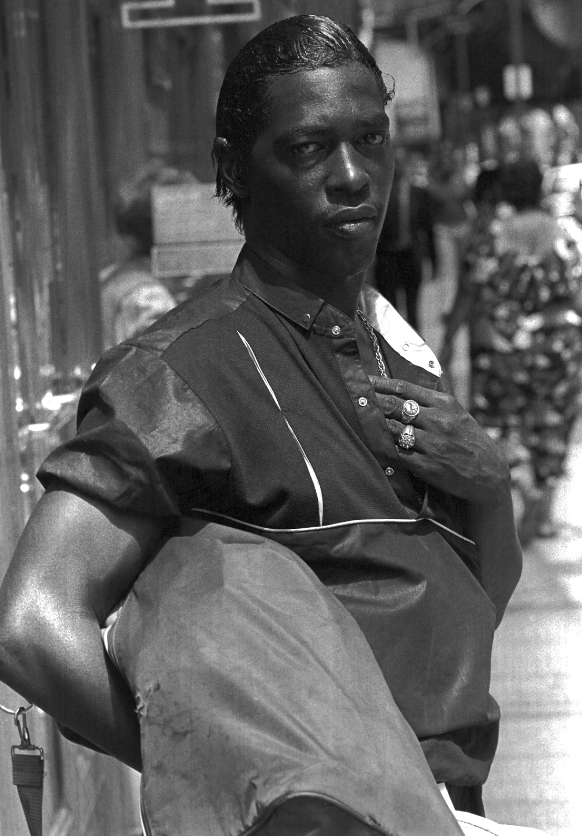

Interlude

He looks straight into the camera with fixed eyes and pursed lips, the light glints on his forehead and slicked back hair. Left hand raised and curled to gently touch his chest through a buttoned-down shirt, two rings adorn his fingers. His right arm cradles a bag that extends out of the frame. Even with the intensity of his eyes, there is a softness in his stance.

“They spoke of themselves using verbs, they didn’t use nouns”

Voices spill out from different rooms of Patric’s apartment, each carefully assembled with art. His Sunday brunches bring together friends, many of whom have known each other for decades. I feel fortunate to be with them, listening to their thoughts on the current state of things in Chicago, recounting new and old gossip, and sharing life updates. Intermingling scents of food waft from the kitchen, with those confident enough to cook a dish for the serious critics describing what they made. On a few occasions, the conversation references Patric’s photographs, and one of the binders is brought out to go through. Varying memories emerge in those moments, as friends bounce off one another in their recollections of people pictured or their own experiences of that time. Invoking the names of some of the men in the archive brings their presence into the room, bending temporal boundaries between past and present. The photographs constitute an “archive of feelings,” following Ann Cvetkovich, which she describes as, “cultural texts as repositories of feelings and emotions, which are encoded not only in the content of the texts themselves but in the practices that surround their production and reception (2003:7).” [3] The images extend beyond what is seen in the frame, becoming sites of projection for the viewer’s own experiences and the memories of the lives of others.

“People will say whatever they want,” Patric replies when I ask how he hopes his archive is engaged. He is not interested in controlling the narratives associated with the photographs. He does, however, consider the potential of the archive to expand more nuanced discussions of same-gender desiring men, especially Black men. “They spoke of themselves using verbs, they didn’t use nouns,” he remarks, complicating the fixation on correlating one’s sexual acts and desires with an identity. While there was less open discussion of sexuality among men in the 1980s, he stresses a certain freedom that came from exploring what one enjoyed sexually without having to categorize it as a distinct identity. In a conversation with cultural critic Anita Naoko Pilgrim, Ajamu X expresses similar frustrations with the overdetermination attached to identity politics, and the self-imposed boundaries they can construct around sex and pleasure. Rather than be dictated by identity categories, he describes his practice as delving into the gray area that exceeds definition, noting, “My aim was to side-step some of these discourses, and to re-think the space in between, the multiplicity of the in betweenness” (2003: 110). [4] This affirmation of multiplicity is resonant in Patric’s view that there is much unspoken in the images: “You can’t imagine looking at these pictures, who these men were.” The photograph is not a document of an absolute truth, and Patric’s reflections on the encounters that surrounded them gesture to the richness of experience that seeps into that in-between space that Ajamu describes, one which an identity category can never hold.

Interlude

They look into each other’s eyes, one man’s back is turned to the camera, the waves in his hair prominent with a tiny whisp of hair at the nape of his neck decorated with beads. Only a section of the other man’s face is visible, as he smiles and looks intently at his companion. His hair is shaved short, with a slight contrast between the side and top of his scalp. Perhaps they know each other well or this is a chance encounter. There is a clear connection between them, even if momentary.

A Constellation of Erotic Connections

While we have not discussed it at length, spending time with Patric’s archive, one cannot help but slip into contemplation about the impact of the HIV/AIDS crisis, since most of the images were taken during the height of the epidemic in the 1980’s. Depending on one’s perspective, the archive may also carry undertones of grief as a record of lives lost. Patric recalls: “There was an awareness of certainty of your mortality… you’re seeing people die who did the same things you did, with the same people…you had a sense that this could happen to me and you had to come to grips with that.” He also emphasizes that people were still having sex amidst the anxieties of this moment, “We still had sex, but it was strange…then the sort of safe practices started to come into play. People were asking, I only do it this way…That was there.” That juxtaposition echoes the ethos that he has consistently espoused: a recognition that sex is a mode of being together that sometimes defies the fears that accompany it, including the reality of one’s death. “I look back and recognize that there’s some strength in me that got me through that I wasn’t fully aware of, but that I could tap into to get through.” An incomprehensible depth remains heavy in the space between us. For while I hear Patric’s words, I will never be able to grasp the experience he describes, unfathomable loss that has left an indelible impression.

I began conceiving of this essay to consider the potential of lingering with an archive, attending to the emotional and physical resonances that stay with the viewer through the multiple returns to the images. How does the archive, as a repository of feelings and memories, invite introspection into the interior dimensions of a subset of Black life? In this instance, it is the experiences of Black men who desire men in the 1970‘s and 1980’s in Chicago. Many may turn to Patric’s photographs as a site of Black gay representation, highlighting the importance of visibility. While I recognize the inherent value this brings, I do not approach Patric’s archive solely as a means to bring visibility. Evelyn Hammonds writes, discussing a lack of critical discussion of Black women’s sexuality, that visibility in and of itself is limited without a “politics of articulation” that seeks to interrogate power structures and assert more intentional modes of engagement. [5] Patric articulates his position on his archive clearly: the photographs are mementos of desire, for him, the men, and the sexual encounters they experienced. It is a constellation of erotic connections.

Notes

Muñoz, José Esteban. "Ephemera as evidence: Introductory notes to queer acts." (1996): 5-16.

Ajamu, Courtnay McFARLANE, and Ronald Cummings. "Promiscuous Archiving: Notes on the Joys of Curating Black Queer Legacies." Journal of Canadian Studies 54, no. 2-3 (2020): 585-616.

Ajamu, X., and Anita Naoko Pilgrim. "In Conversation: Photographer Ajamu and Cultural Critic Anita Naoko Pilgrim." Paragraph 26, no. 1/2 (2003): 107-118.

Cvetkovich, Ann. Archive of feelings. Vol. 2008. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Hammonds, Evelynn. "Black (w) holes and the geometry of black female sexuality." In The black studies reader, pp. 313-326. Routledge, 2004.