Being Otherwise: Notes on Black Feminist Relationality in Sola Olulode’s Where The Ocean Meets The Beach

(Originally published in ARTS.BLACK)

“A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or non-sexually. Appreciates and prefers women’s culture, women’s emotional flexibility and women’s strength… Loves the Spirit… Loves struggle. Loves the Folk. Loves herself. Regardless.”

Alice Walker, “Womanist,” In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983)

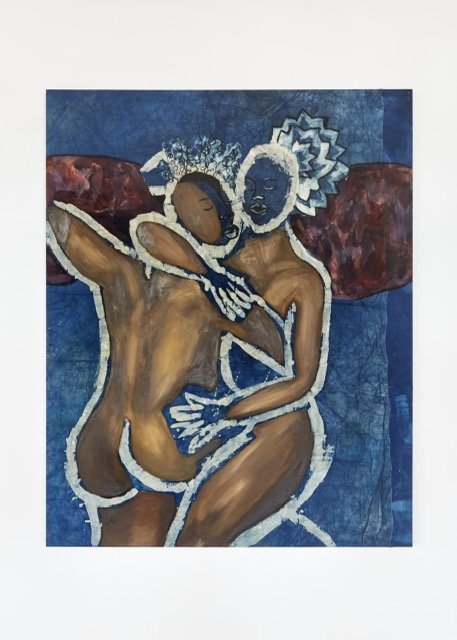

Entwined, 2020

Ink, oil, and wax on canvas

Courtesy the artist

Brown limbs melt together, shaping into the bodies’ grooves and surrounded by the blues of the indigo-dyed background. The faint creases and lines are a system of roots, heads cradled in maroon petals. Right arm encircles her neck, left hand rests on the fleshiness where the buttocks meets the thigh. Faces touch as the womxn 1 embrace with eyes and lips closed. Hair is soft, curling black lines. A flower blooming from the scalp. The energy is feminine, existing in the “deeply female and spiritual plane” that theorist and poet Audre Lorde terms the erotic 2. British Nigerian artist Sola Olulode titled the piece Entwined as part of her recent exhibition Where the Ocean Meets the Beach at VO Curations gallery in London.

In my reflection on Olulode’s work, I return to the reading practice laid out by Black feminist theorist and activist Barbara Smith in “Towards a Black Feminist Criticism” (1979), intentionally attending to relationships of sensuality between Black womxn—whether romantic, sexual or otherwise—that are often overlooked in analyses limited by heteronormativity. 3 Smith cites the Radicalesbians manifesto “Woman identified woman”, which gestures towards a broader understanding of lesbian: “What is a lesbian? She is the woman who, often beginning at an extremely early age, acts in accordance with her inner compulsion to be a more complete and freer human being than her society cares to allow her.” 4 This essay holds space for all the range of expressions of Black womxn’s intimacies 5 and develops alongside visionaries such as Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, M. Jacqui Alexander, June Jordan and Kevin Quashie, drawing from their synergy with Olulode’s work. I situate Olulode’s work within a larger discussion of Black feminist perspectives on intimacy and relationality that are the ways of loving, being with others, and collective consciousness that I learn from most and yearn to see in the world. It is my relationships to Black womxn and femmes that have allowed me to honor my own femme-ininity 6 as a Black queer man, while also reckoning with the fact that my position within masculinity is often predicated on the societal denigration of Black womxnhood. I invite readers to grapple with the intentional work necessary to create a world in which Black womxn and femmes can exist in the richness of their interior lives.

Through her paintings, Olulode conjures the erotic in an embrace of the feminine with an acute attention to intimacy. She employs the Yoruba resist-dyeing technique Adire 7 following in the histories of womxn in South-Western Nigeria, and treats different parts of the canvas to create the desired colors. Her attention to the dimensions of Blackness engage it both to denote race and as a structuring racial logic, noting in an interview, “I am also interested in the relationship between Blackness as a colour, and identity.” Her use of blues to depict skin color, as shown in the pieces Entwined and In the Middle, relates to notions of “blue-black” as discussed in art history 8 and African-American culture. The term is used both to characterize the depth of the colors of dark-skin and examine the nuances of Blackness beyond skin tone. It is explored by artists such as David Hammons in Concerto in Black and Blue (2002)and Carrie Mae Weems in “Blue Black Boy” (1997). As Glenn Ligon writes, regarding his exhibition “Blue Black” (2017), “Blue-black is the kind of black where you go, “Black!” 9

Olulode’s brush strokes take on hatching and shading techniques, creating an ethereality to her figures. Her use of melted wax adds texture and structure to the bodies and patterns, their features etched and outlined with bleach. Her hands bring an intimacy to the canvas through dyeing techniques, working and stretching it while covered in indigo and turmeric. Employing charcoal and collage highlights the dimensions of tactility. Olulode’s paintings do not feel heavy handed or over-worked. Their lightness orients me towards my own vulnerability, engendering a softness to my movements and an awareness of my physicality. I follow the breath that animates my body as I move through the room. Tread lightly and do not seek to harm.

Entwined is the first piece I am drawn to in the exhibition in the twelfth floor gallery. I am alone, the sun streaming into the windows, providing an escape from the grey of London. The paintings generate a warmth I rarely find in galleries. “Sometimes I stand by the edge of where the ocean meets the beach and look out into the sea, so I can feel like something that does not have an end.” Olulode draws her show’s title from this line in artist Travis Alabanza’s poem “The Sea,” in which they connect the freedom to express one’s gender and its possibilities to the vastness of the sea. The poem illustrates the malleable possibilities of gender, or no gender, and the ways Black people inhabit these experiences, making them their own. I both attend to Olulode’s work as a meditation on intimacies between Black womxn and femmes specifically and adamantly believe in Alabanza’s discussion of the expansiveness of gender. 10

Olulode and Alabanza express the spaciousness of the Black diaspora, interlinked by oceans and seas, archipelagos and continents now divided. Olulode’s use of Adire and vivid color schemes of blues and yellows invoke the orishas Yemọja 11 and Ọṣun, 12 protectors of womxn and femmes. 13 The dyeing technique is historically known for incorporating motifs of indigenous and contemporary Yoruba life, such as philosophy and religion. Sitting with her work, my body recalls feelings experienced at a celebration of Ọṣun in Trinidad and Tobago several years before. 14 We sought her presence on the sandy banks where the Salybia river intertwines with the Atlantic Ocean. I lost count of the womxn and femmes mounted by her spirit and entering the waters. What memories lie at the intersection where the ocean meets the beach, where Alabanza’s words wash onto Olulode’s canvas? 15

My eyes plunge into the yellows of the diptych The Feels. The womxn look at each other in profile, illuminated by a brilliant sun. Hair streams down her torso. Her head is crowned with an afro. They wear a yellow sleeveless blouse and an orange tube top. Eyes open or closed, I cannot tell. And yet I am acutely aware that they see each other. The colors of their bodies like photo negatives, revealing an interiority that emanates throughout Olulode’s work. Their bodies merge together in the scene below, faces enmeshed in hair. Naked, but not exposed. Her hand rests on her shoulder and fits in the center of her back. They could be lovers, friends, sisters. They are with one another. I understand this notion of with as a type of presence that extends beyond physical proximity. It is rooted in Black feminist theories of relationality and the spirit, following scholars such as Lorde, 20 Jordan, 21 and Jacqui Alexander. 22 It is a recognition of the complex existence of another. I see you. In a conversation with the Signified series, 23 series, Jacqui Alexander notes:

The source of our connection is a deeply spiritual one. It’s a divine connection. It’s that mirror connection that Audre talks about a lot, too. The fact that you are reflected in me, and I in you, and the source of that, I believe, is a source that is divine. That source is the source of spirit.

Interrogating this connection that Jacqui Alexander highlights fuels my desire to delve into the concept of relationality, now more than ever. The stakes are collective survival, and to disregard that is fatal. This relationality is embedded with the divine force that Lorde calls the erotic, a source of power, information, and connection with others. Opening to the potential of the erotic involves a sensuous excess, 24 a willingness to explore the depth of intimacy with self and others. Lorde’s erotic is another name for Walker’s discussion of love in her definition of womanist, an inclination to be open to the complexities of the Other.

In her envisioning of the term “womanist” in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983), Walker writes, “A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or non-sexually. Appreciates and prefers women’s culture, women’s emotional flexibility and women’s strength… Loves the Spirit… Loves struggle. Loves the Folk. Loves herself. Regardless.” 25 “Loves” is italicized twice when referring to “spirit” and “folk”, and “regardless” is italicized once, encompassing all that is said. Regardless holds space for tension, feelings that often emerge in Black feminisms and seeks to find a meeting ground despite, or because of, intentional acknowledgments of difference. 26 To live in the world and recognize that one’s body is profoundly connected to each and every other body is difficult, the gravity of it almost unimaginable. And yet we must strive to do it regardless. To love the Folk is an affirmation of communal living. It is central to Black life, and in Walker’s context, recognizably Southern.

Love is integral to womanism and has come to represent a tenet of my engagements of Black feminisms more broadly. Throughout her work, Jordan explores love as theory and praxis, proclaiming “love is lifeforce” in her text “The Creative Spirit and Children’s Literature.” 27 This theoretical framework is amplified by contemporary Black feminist scholar Alexis Pauline-Gumbs in the manifesto “What We Believe: Love Made Manifest,” which states “Love is all that supports life… Love is a serious and tender concern to respect the nature and spontaneous purpose of other things and people… Love is lifeforce.” 28 Black feminist scholar Jennifer Nash analyses discussions of love in “second-wave” Black feminism as a “strategy for remaking the self and for moving beyond the limitations of selfhood (2011:3).” 29 bell hooks similarly highlights the relationality of love, writing: “when we choose to love we choose to move against fear—against alienation and separation. The choice to love is a choice to connect—to find ourselves in the other”(2000:93). 30 hooks characterizes love as an active decision to develop interconnection with others. The Combahee River Collective situate their politics of liberation as emerging from a “healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community” (1977). 31 Love is theorized as deeply entwined, both in the self and the collective. As I work through the potential of love as theory, I ask what would it mean to understand love beyond scarcity and the romantic, but rather as an approach to being with others? Love must be theorized because it is hard work. To love regardless does not mean to subject ourselves to the violence of some forms of intimacy, but instead to affirm a belief in the wholeness of the Other’s existence.

Memories of quiet moments in a partner’s arms, my body finds a home in yours. Olulode’s work exudes quiet portrayals of intimacy between Black womxn and femmes, providing another narrative to the publicness often demanded of Black life. These moments are a private refuge for Black people who are under constant surveillance. Literary scholar Kevin Quashie interrogates the positioning of Black life predominantly in the public sphere, relegated as performances of the Other to be observed: “So much of the discourse of racial blackness imagines black people as public subjects with identities formed and articulated and resisted in public (2012:8). 32The subtleties of intimacy between Olulode’s figures present a refusal of the public gaze. Though the paintings are on display for viewers in the gallery, it feels like I am eavesdropping on private moments. Discussing this withholding, art critic Olamiju Fajemisin writes, “Olulode’s figures, unheeding because of the attention they give to one another, appear impervious to our gaze. If they look forward, they look past us (2020).”

If you know then you know.

Laying in the Grass 1, 2020

Ink, oil, oil pastel, oil bar, charcoal, and wax on canvas

Courtesy the artist

Laying in the Grass 1, their bodies lie in opposite directions as their faces touch, cradled by a crown of black locs. Soft tones of brown skin. Her hand falls on her bicep, palms upturned. Dressed in a pale orange and sunflower yellow, on a green Adiri background with short brushstrokes of grass. The field is theirs as they rest. Rest is essential. Quashie highlights the inability for Black womxn and femmes to simply be in the world and to care for themselves, without the constant pressure to do so for others: “The right to be nothing to anyone but self—this is the right that black people, and black women specifically, don’t get to inhabit (70).” I think about the work needed to create spaces for Black womxn and femmes to access quiet as a form of self-preservation. Walker emphasizes these acts of self-care, describing a womanist as “not a separatist, except, periodically, for health” (1983:11). Poet and scholar Elizabeth Alexander speaks to the possibilities made available through this move inwards: “Tapping into this black imaginary helps us envision what we are not meant to envision: complex black selves, real and enactable black power, rampant, and unfetishized black beauty (2004). 33 It is through this beautiful imaginary that otherwise living becomes available.

In the Middle, 2018

Oil, acrylic, oil pastel, wax, charcoal, and collage on canvas

In the Middle, they dance close together, painted in shades of brown, black, and blue. Each has a different outfit: a green crop top and joggers, a fuschia tube dress. Some womxn have arms raised in the air, others closer to their sides. Legs bent, readying the wining waist movement of the African diaspora. Some hold up cell phones to take selfies. The relationships between the womxn are not explicit, but the energy is collective, embodying what Walker identifies as a sign of womxn’s culture. 34 This concept of womxn’s culture animates the history of Adire dyeing techniques, invoking over a century-long practice of Yoruba Nigerian women working collectively to produce and distribute the cloth. In “Uses of the Erotic” Lorde claims that these connections are a form of consciousness that arise from collective existence: “As a Black lesbian feminist, I have a particular feel-ing, knowledge, and understanding for those sisters with whom I have danced hard, played, or even fought. This deep participation has often been the forerunner for joint concerted actions not possible before (1978:91).” Erotic relationships, imagined broadly, become a catalyst for collective action—a site of possibility. In a studio visit with the art publication boundary, Olulode notes, “my relationships with womxn and femmes are the most important to me in life as they are the people I relate to the most… I want to depict all these different relationships that I witness.” Olulode’s portrayal of Black womxn’s culture generates an affective pull that draws me to her work, even in the opacity created through techniques of abstraction in the painting of the figures.

I find beauty in the absence of specificity of facial or bodily features in Olulode’s pieces. Though her work is inspired by personal experiences, there is subtle abstraction in the simpler human forms, producing an obscurity that allows them to translate beyond the limits of specificity and foster an empathic engagement that resonates between viewer and the image. Philosopher Édouard Glissant considers opacity integral to a poetics of relation that holds space for difference. Opacity may breed obscurity through the inability to demand transparency, but understanding the other does not necessitate reduction. I participate in Olulode’s paintings precisely because I cannot know the figures in their entirety; rather, I come to them and create meaning through my own experiences of the world. Her engagement of opacity moves me in ways similar to several other Black womxn artists, including Chicago-based Brittney Leanne Williams, 35 London-based Davinia-Ann Robinson, 36 and Trinidad and Tobago-based Brianna McCarthy. 37 Each interrogates the boundaries of the body, desire, and intimacy in ways that center Black womxn and femme subjectivity, employing abstraction while wrestling with the materiality of Black embodiment.

Eternal Light, 2020

Ink, acrylic, and wax on canvas

Courtesy the artist

We Are All in Relation

She reaches to grasp the arms wrapped around her back, four hands clasped together. Cheeks lean together, eyes and lips closed. Braids fall down the side of one face, the other has an afro crown. Brown skin covered by red dresses patterned with drops of orange. Bodies immersed in the sunbeams of the yellow background, they hold each other tightly. I read “Eternal Light” as a mother and child, but perhaps it is two friends or lovers. The way they hold each other is protective. I got you. Olulode’s work holds Black life gently, without insisting on a performative Black subjectivity for viewers. She does not reproduce the often binary position that limits Black existence solely as resistance to anti-Black violence. Her portrayals of intimacies between Black womxn and femmes are an avenue towards imagining otherwise lives, putting breath back into our bodies. 38 She cultivates a quiet for her figures to live and be with each other regardless of the violences that surround them. Her work emphasizes the beautiful possibilities of Black interior life.

*We are afraid of touch. Though for some of us, that fear is constitutive of our being in this world. Some are positioned in fear, with the lingering hope that this may change. Touch is filled with anxiety is filled with longing is filled with impossibility. How will we reimagine intimacy and touch when the violences of COVID-19 are once again masked under capitalism and anti-Blackness? I believe some of us will search for other ways, because we have always been searching.

Notes:

I am grateful for the support and insight of the Northwestern University Black Arts Initiative graduate working group for their support in reading and providing feedback on this essay.

I am grateful for the support of Candice Merritt and Tavis Vera in providing extensive feedback and edits for this essay.